Live here long enough and you’ll learn the sure-fire signs of spring in Philadelphia.

Grapefruit League baseball on WIP, East Passyunk happy hours al fresco, those funky-smelling trees dotting Center City and better-smelling (well, to some at least) exhaust barks bouncing down canyons of cement and steel. One usually finds that latter soundtrack – for better, worse or indifferent – coming from roving packs of off-road vehicles roaming the very on-road Broad Street.

It is, as they say, what it is. It has also been a long, long time since the city of brotherly love and sisterly affection hosted completely condoned dirt bike racing within its 142 square miles. This makes the Monster Energy AMA Supercross date at Philadelphia’s Lincoln Financial Field on April 27 rather significant.

For one, it’s the first time in 44 years that somewhere in South Philly’s stadium district, a sprawling sea of arenas and asphalt, really mean motorcycles will roam the maliciously bulldozed earth.

Let’s hope this latest addition to the tradition becomes another tell-tale sign of seasons changing.

And two, an even earlier incarnation of today’s distinctly American indoor racing phenomenon was held in late 1973. With this golden milestone, Philly beat just about every other present-day host to the much-ballyhooed 50th anniversary punch.

“All these years later,” one spectator turned competitor reflected on yet another dreary Friday afternoon in the depths of winter 2024, “I’m standing in my shop surrounded by motorcycles.”

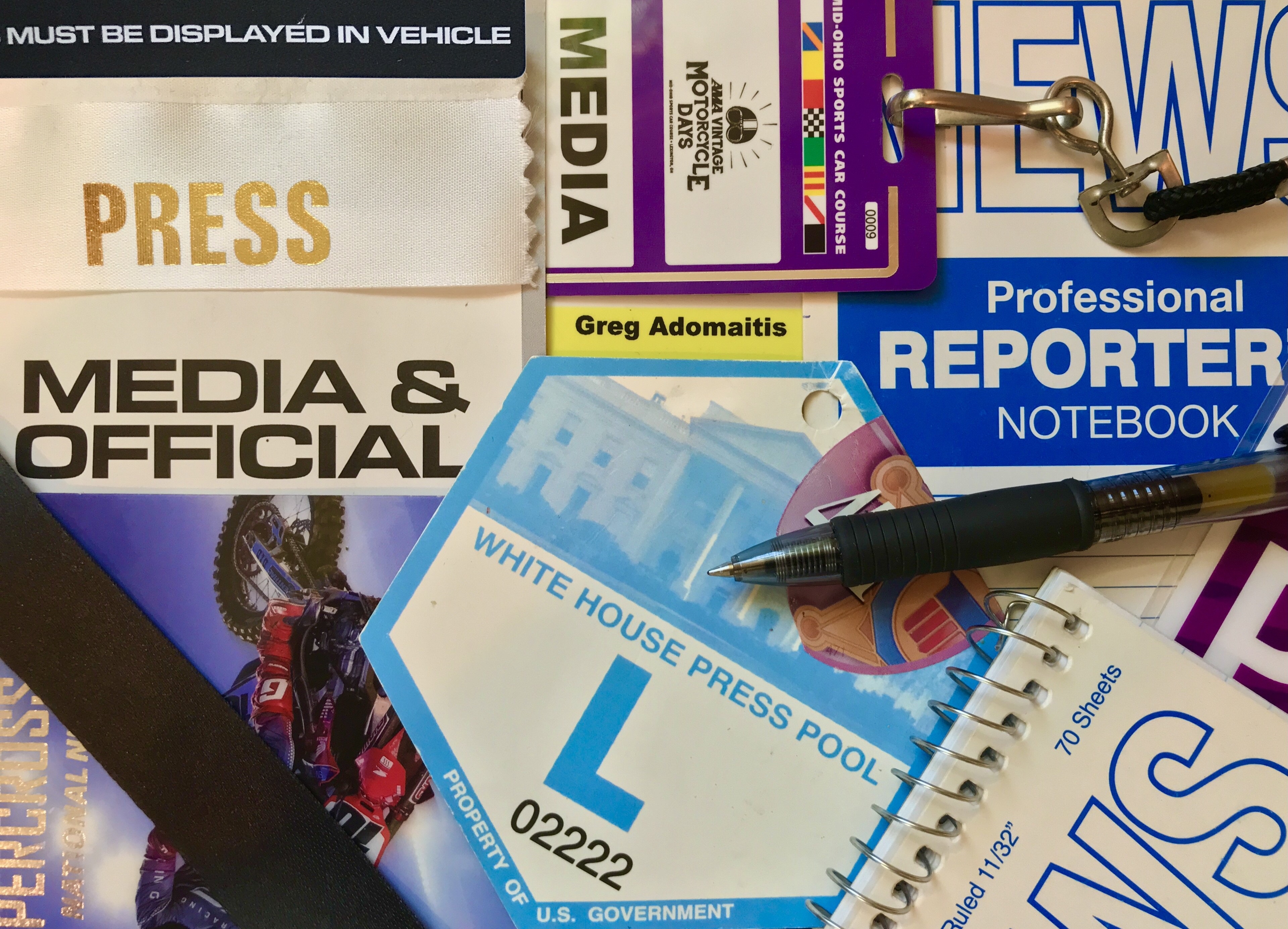

For some, the memories are as vivid today as they were decades ago. For the rest of us, there’s always YouTube. So let’s turn back the time machine to hear the perspectives of patrons, promoters and privateers who helped cement those Supercross building blocks at the long-since demolished John F. Kennedy Stadium.

The Prodigal Son Returns

It was an idea in its infancy, but a near-immediate game-changer nonetheless, and Daytona International Speedway would host a trial run of sorts in 1971. “While most motocross races had been held in the remote, rural countryside, Daytona brought motocross to where the fans already were,” reads an American Motorcyclist Association (AMA) primer on the discipline we’re discussing.

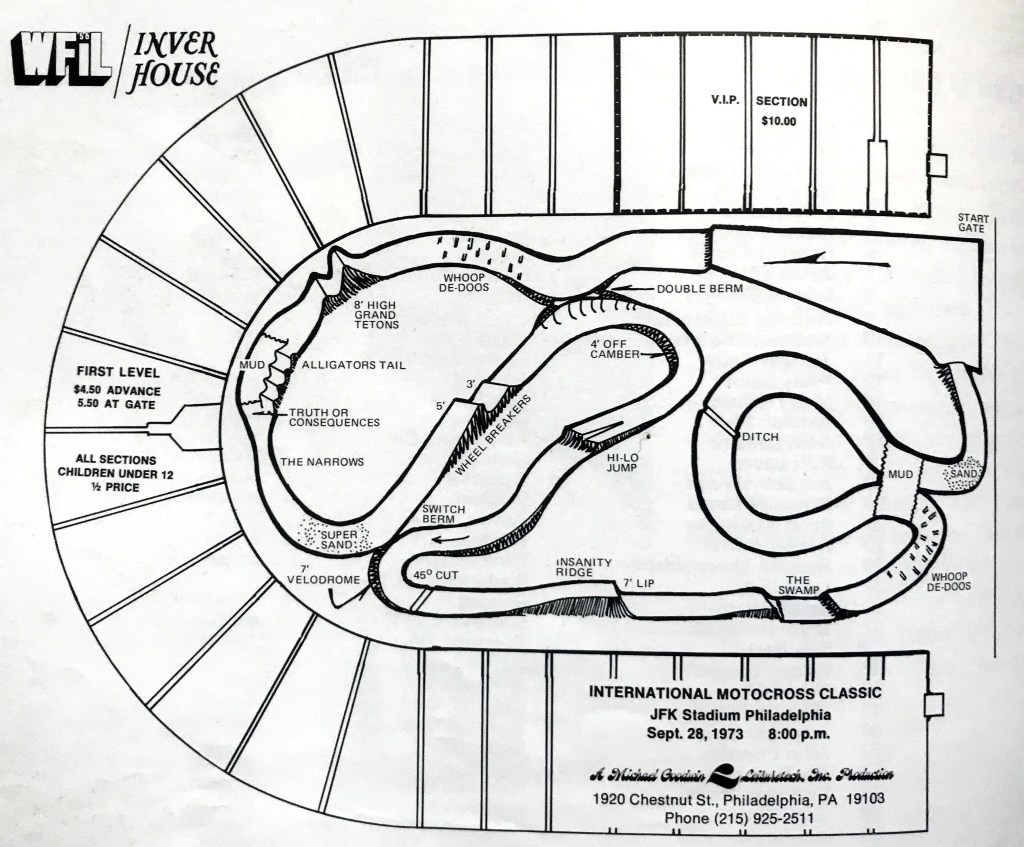

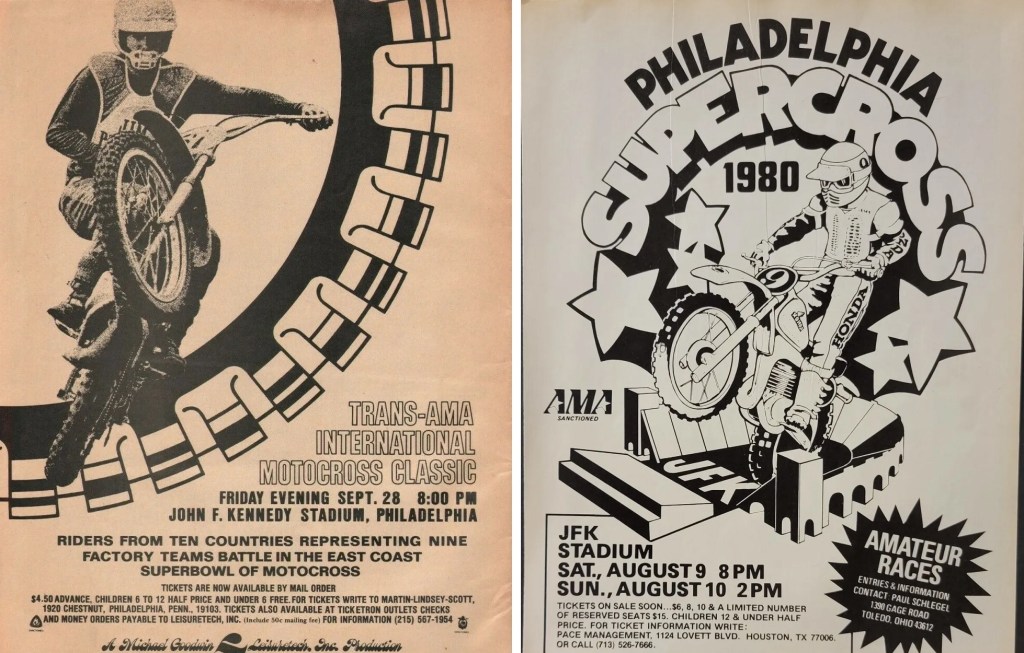

Promoter Mike Goodwin enjoyed additional success with his landmark Super Bowl-style indoor motocross mash-up at the Los Angeles Coliseum in 1972. Through a half of a half-dozen more non-traditional infield races at Road Atlanta, Pocono and Talladega, the shape of things to come came into view by ’73 when the big show arrived in Philadelphia that September evening as part of the Trans-AMA series.

It wasn’t technically “Supercross” yet, but we traded stock car stomping grounds for an indoor setting (also the second-ever night time stadium race) and some bike-breaking, points-paying and audience hooliganism drama that left the AMA none too pleased. There were fewer hiccups shortly thereafter and the motorcyclist association changed gears to officially sanction a real-deal championship series in ’74. The race was on – even if it was only three rounds that year. As some cities across the country clamor to claim 50 years of Supercross inside their pantheons of power, Philly, the wayward underdog and prodigal son, sneaks in with 51 under its kidney belt.

Inquiring minds want to know then: why now – and where ya been? It’s a question we put to Feld Motor Sports, which produces the big show, but they did not respond to our request for comment. There’s nothing on MetLife Stadium’s schedule up the road in East Rutherford that would conceivably conflict with hosting another round this year. That said, our money’s on this two-for-one special: Feld’s own Monster Jam truck rally is slated for the Saturday following Supercross so that’ll keep the dirt works crews conceivably bang-for-the-buck busy reconfiguring things down at the Linc.

‘Like Falling out of a Two-Story Window’

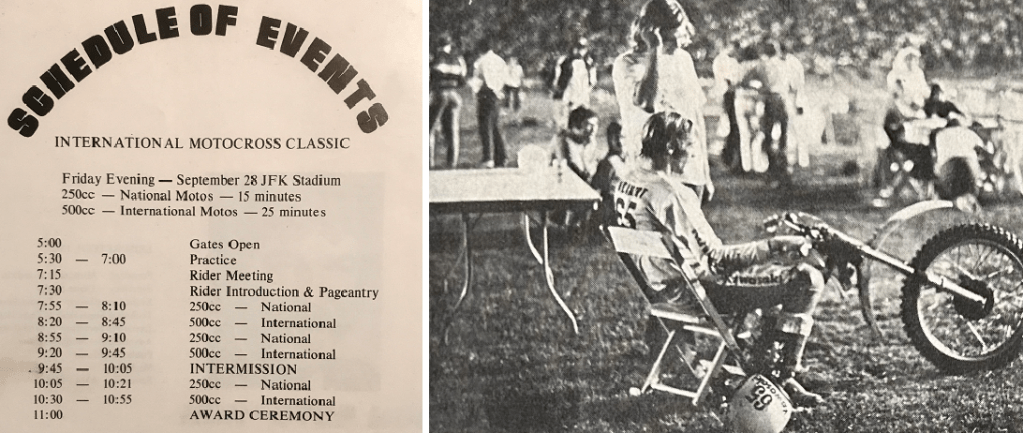

Today, the Philadelphia Flyers play professional ice hockey in the footprint of the former JFK Stadium. Things have changed just a bit since Motocross Action set the scene for us. All the fast-movers, earth-shakers and European ironmen of the era were on hand the evening of Sept. 28, 1973 to go racing under the open-air horseshoe-shaped stadium’s semi-bright lights. It was new, it was flashy, it was Friday night and Elton John was playing across the street.

More importantly, it was very different from the European-style wide-open outdoor courses that were the only game in town at the time.

- MXA‘s track talk said this short circuit, with its deadly “Grand Tetons” jumps, clocked 40-second lap times.

- Cycle World shoveled on the complaints, saying the rock-laden and dusty course was “a masochist’s delight.”

- Modern Cycle drove the last nail in, saying it was more “destruction derby” than motocross.

If that’s the case, Jim Scaysbrook, veteran multi-discipline racer (even the Isle of Man TT) and editor of Old Bike Australasia magazine, closed the casket. He had a lot more to tell me about the conditions down on the Army-Navy football game’s grid iron ground floor that fateful Friday evening.

“Whoever constructed the track had little idea of what it is like to race a motorcycle.”

“You have to remember that this was in the very beginnings of the rear suspension revolution, although the majority of the field in the early 1973 Trans-AMA rounds were still on stock bikes with conventional suspension,” Scaysbrook, whose full ‘73 experience is recounted here, said earlier this year. “By the end of the series, just about all the bikes had been modified in some way,” he continued – but not his.

“I remember at one round a guy turned up with Ake Jonsson’s ex-works Maico, on which Ake had won the 1972 series, unchanged from that specification,” he continued. “Somebody was looking at it and said, ‘When are you gonna change the rear suspension?’ to which the owner answered, ‘When I can ride it as fast as Ake did last year.’”

To compete in the ‘73 series, the first Australian to do so, the open class international pro and his campaign compatriot, Laurie Alderton, would ship their bikes from down under and buy a van while state-side to make it all happen. Philadelphia, the second stop in the 11 rounds of racing, proved quite the evening and was book-ended by blowing up wheels, borrowing parts and breaking them all over again.

“Maico, Maico, made of tin. Ride it out, push it in,” the guardian angels seemed to sing. That the official $2 souvenir program dubbed a 5-foot-tall step-down double jump a “Wheel Breaker” really just adds insult to injury.

“Whoever constructed the track had little idea of what it is like to race a motorcycle. The jumps were gigantic with a run-up ramp, but with a sheer drop at the face, straight onto a flat surface – it was like falling out of a two-story window,” his tour tale reads. “It took only a few laps of practice to destroy both wheels in my Maico, so it looked like a night of spectating, until a very large chap smoking a very large cigar strolled up to me in the pits.”

“Sitting on a rack on his very large motor home was another Maico and he told me to take whatever I needed to get mine going. I thanked him, but said it was very likely that whatever he loaned me would end up smashed, to which he replied with a roar of laughter and a slap on my back, ‘Hell, son. I got plenty more of ‘em at home. Don’t matter a damn to me!’ A bit of frantic spanner work later and half his bike was installed in mine in time for the first race, and true to form, it lasted about half the first leg until the wheels exploded.”

Ah, Philadelphia. Brotherly love, indeed.

“You can see from the photo that the grandstands were full, as was the car park, with big motor homes everywhere, so I guess there was plenty of ‘atmosphere,’” he said when asked about his evening in Philly. Problem was, “I was probably too busy rebuilding bikes to notice it.”

With Stars in their Eyes

At 13 years old and carted from South Jersey to South Philly by his mother, Scott Stevens was among the 15,000 (a little less than half of the ‘72 LA Coliseum headcount depending on who you ask) in the grandstands that late September night while the likes of Scaysbrook worked feverishly to get back in the action. None other than Captain Kirk (actor and actual motorcycle enthusiast William Shatner) descending from the final frontier via helicopter to wish the racers luck and a live music act (Stevens thinks it was Grand Funk Railroad) whipped the crowd up.

It was the era of Elsinores, half helmets and all-around exemplary of motorcycling’s exploding popularity. What stood out to Stevens spectating his first-ever big race, though, was the well-oiled industry in action – namely the very recent launch of competition-only MXA from the offices of headlight-friendly Dirt Bike.

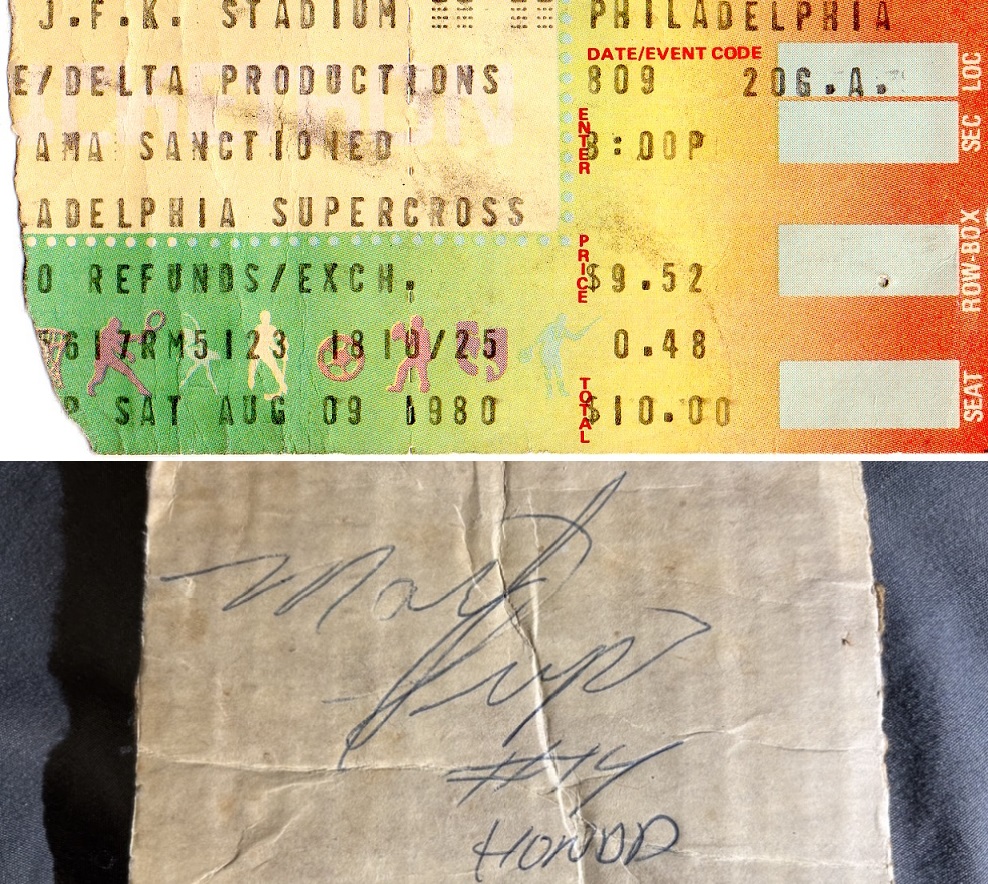

From reading these issues as a teen, Stevens learned the origin stories of DeCoster and Weil alongside the domestic likes of Lackey and the very local DiStefano. It was boy wonder Marty Tripes, however, whose signature he scored after jumping the stadium wall at the end of the night, finding him in the pits and utilizing the top of a errant cardboard box. He’s still got the memento, naturally.

“I was just hooked,” Stevens said of his impression of the evening’s entertainment, adding that he went back to his family’s four-acre property and built a replica of the Philly course – ski jump and all – and its features lasted long after the family sold the house. “To those guys, it wasn’t even a good stadium track,” he emphasized. That didn’t matter a good god damn to a 13-year-old just getting into motocross and seeing the trick machines and pro riders whose exploits, up until this point, only existed on glossy paper at monthly intervals.

Even Paul Clipper, whose byline would soon appear in some of the same magazines Stevens lauded as being so instrumental, was just another young spectator that night. This was four years before Clipper “got the opportunity to run out to California and claw my way into the motorcycle industry” and while he admittedly wasn’t a big racing fan at the time, he, too, was learning about the big guns via whatever periodicals a friend would come home with.

‘Here was actual professional dirt bike racing, right out here where we could touch it. It was real, and in some way we were a part of it, a part of that whole big family.’

“The racers back then were colorful, all different in their approach to the sport, and the magazines back then painted them all as interesting characters,” the former Trail Rider Magazine publisher said recently. To his point, Weinert’s escapades with his decapitated motorcycle – a factory ride, no less, but still within the realm of possibilities – solicited plenty of confusion, then laughs, from the crowd as he “jumped out and rolled that front end past the checkers.”

As with most topics of this era, the seemingly omnipresent, and then recently-released On Any Sunday, gets its due yet again. The film’s portrayal of a global extended family offered overnight validation, Clipper said, for those who right up until that moment were just crashing around on clunky bikes in the woods and sand pits.

“The 1973 stadium race at JFK in Philadelphia had the same sort of effect,” he added of the film’s impact. “Here was actual professional dirt bike racing, right out here where we could touch it. It was real, and in some way we were a part of it, a part of that whole big family.”

Young Forever

Ever the salesman, Goodwin promised the ’73 race was the “first annual” – which any journalism school graduate will tell you is not a thing – and that there’d be more to come next year. We’d have to wait just a bit longer than that.

Fast-forward seven years and the circus circles back around on the dilapidated JFK Stadium, parking itself there for two full days of competition in August 1980. The wheelie king, Doug Domokos, did his thing, the Phillie Phanatic apparently crashed into a sprinkler head while riding a three-wheeler and there were gate drops going down close to midnight. Stevens had worked his way up to bona fide racer in the meantime while Supercross, now with a capital “S,” had firmly established itself. And yet…

“It was literally the worst track I’ve ever ridden,” laughed Stevens, a veteran 125cc pilot who held a pro license at one time in his motocross career. Qualifying for the nighttime expert main event was, as one might expect, a nice personal capstone. It was a shade too dark in the stadium, he said, but “pretty bitchin’” overall… and we won’t argue with that.

This course “seemed to be all whoop-de-doos, whereas 1973 had at least two huge mounds with sheer drop offs – there was no landing ramp at all,” Scaysbrook told me when asked to take a peek at the ‘80 footage, which you can view above at bone-jarring speed. “This was what did all the damage to my wheels and in Jim Weinert’s case, the front half of the frame.”

Jerry Blazek took one look at the same video, started nodding his head and calling out the turns of the 1980 layout before they came on screen then summed up the jump-heavy course with all the diplomacy of a politician: “Demanding.” It wasn’t fast, he elaborated, saying that each 12-lap heat was a sufficient skills test that barely covered one-quarter of the available footprint while also offering an experience unlike anything else given the doubleheader stadium setting.

“I built my own car. I raced my own car,” the retired European auto mechanic said. “It’s nothing compared to motocross – and nothing compared to qualifying for open expert motocross. It was in my blood at that point; that was my hobby. I wish I could stay young forever.”

Sport, Survival and the Support Class

On the flyer for the 1980 event, you’ll find an Ohio-based name, phone number and address imploring amateur racers to reach out and sign up. For those playing along at home, Ohio is a long, long way from Philadelphia so it raised an eyebrow. His name was Paul Schlegel. He was a lifelong advocate of all things motorcycling and, and at the end of a day, a monumental figure credited with creating some of today’s biggest races.

“He was not a well-known man, stayed out of the spotlight, and his own words were: ‘I was not a ‘rah-rah’ guy,'” Matt Bucher, president and founder of the Toledo Trail Riders and a driving force behind the 2023 documentary on Schlegel, offered. “However, without Paul, our sport would not be where it is today.”

The accolades laid at Schlegel’s feet, as given by Racer X Magazine when he passed last year, help prove that point. The publication lauded him as “a pioneer in bringing prominence and prestige to the sport during its infancy in the United States,” including the current version of stadium Supercross. Despite this behind-the-scenes role, Schlegel’s impact was felt far and wide, earning him a 2023 AMA Hall of Fame nomination.

As for Philadelphia, neither Bucher nor film producer Todd Staton could recall Schlegel ever speaking specifically about the 1980 race. Still, I had to ask, given the lackluster reviews documented above: Schlegel was in no way a course designer, so send your ill will elsewhere.

‘The sport or industry does not survive without race promoters

who have the guts, taking a chance.’

With that out of the way, “one of the unique things that Paul pushed for was to offer amateur Supercross racing,” Bucher said. “Paul was all about the amateurs getting a chance to ride the same track as the pros! They had 1,345 amateur racers at the Pontiac Supercross one year … which is unreal to think about.” For context, that’s more or less the amount of racers who signed up for Unadilla’s 2023 MX Rewind – and that requires every second of sunlight to cram in a riders meeting, practice, plus two, four-lap, 10-minute motos.

Yeah, Mike Bell and Broc Glover took home the 1980 wins in Philly, where a meager 20,000 attended, but a long list of homegrown talent were also able to sign up thanks to folks like Schlegel. Asked about this support role, Bucher didn’t mince words. “In my opinion, the promoter is the most critical key or component to the Supercross/motocross racing industry… oh, and whom by the way carries the most risk,” he said, adding that no big names can build their legacy without events to do so at. “The sport or industry does not survive without race promoters who have the guts, taking a chance.”

Chaos Theory

Today’s top guns lining up at the Linc will help weave a long-running story that despite only having three chapters, spans time and space – or whatever Captain Kirk might say. The brotherhood of bikes, that whole big family born by Bruce Brown, is a bit too brutish for the “butterfly effect” comparison… so some call it “chaos theory.”

A duo from Australia decides 51 years ago to cross continents and go racing, taking them to Philadelphia of all places. A kid from South Jersey is in the stands, likes what he sees, then lines up on the gate seven years later at the very same stadium. A promoter from Ohio puts his good name on the line to help make it possible. A former co-worker bumps into an old boss in East Rutherford, landing us some lanyards for a free track walk. A swap meet vendor in Pennsylvania sells an old bike fan an old Dirt Bike issue for a buck, and it sparks a conversation elsewhere with a former staffer and fellow writer.

Who knows – maybe some other “old” bike fan from the far-flung future, enamored with the final days of four strokes before the RC cars took over, starts pulling at threads and looking for clues littered all across their backyard. They’ve got a ticket stub from April 27, 2024, a few races on their own resume and they like to listen when people talk. There’s a story to be told, they swear, and some faded autographs from the Lawrence gang to go along with it.

It is, after all, the city of brotherly love… and I’d love to read it some day. Beam me up, Scotty.