Laid end to end, they must have stretched for miles. Both sides of the serpentine course were practically walled in with the things as it slipped between sahara sands and native pinelands.

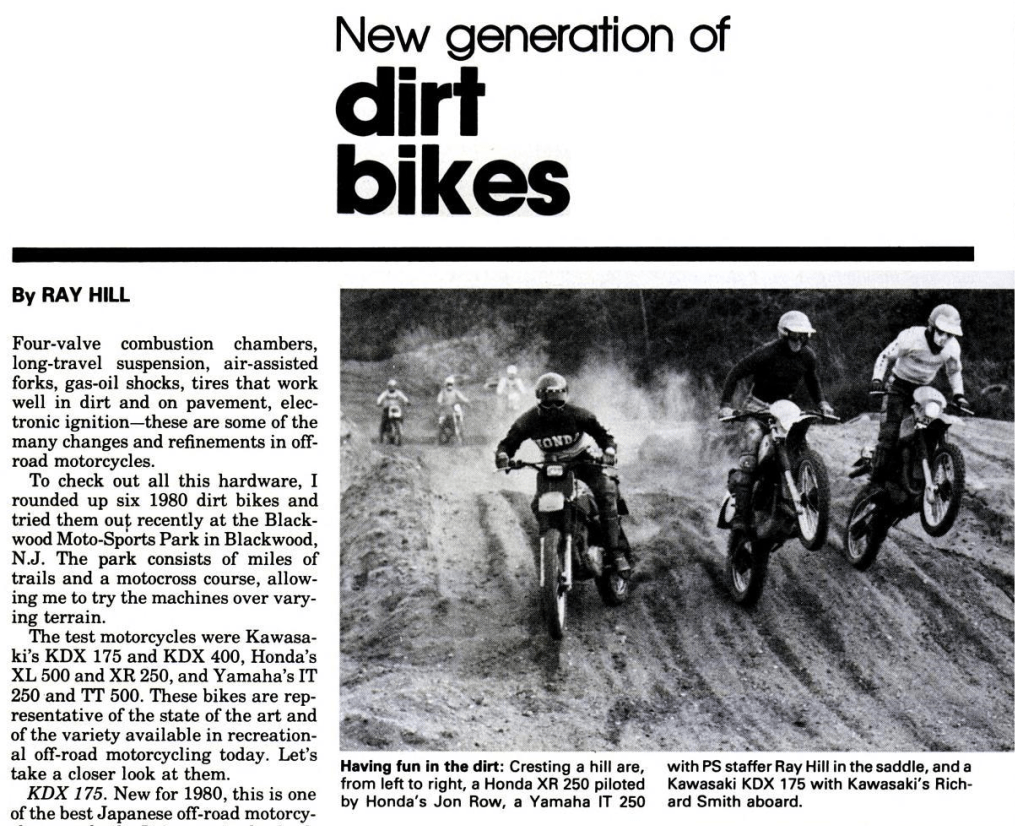

These cracked black car tires, burnt by the sun, half-buried by the wind and strewn to rot by the dozens, are all that’s left to place us in present-day. Out in the woods, a tree has climbed to the sky straight up the center of one while another whitewall set was dug in long ago to firm up a jump. We’re not here to landscape, though, nor raise hell. It’s just a good ol’ fashioned bike test shootout like Popular Science magazine did in this very same spot 44 years ago – naturally upgraded for 21st century stipulations and sensibilities.

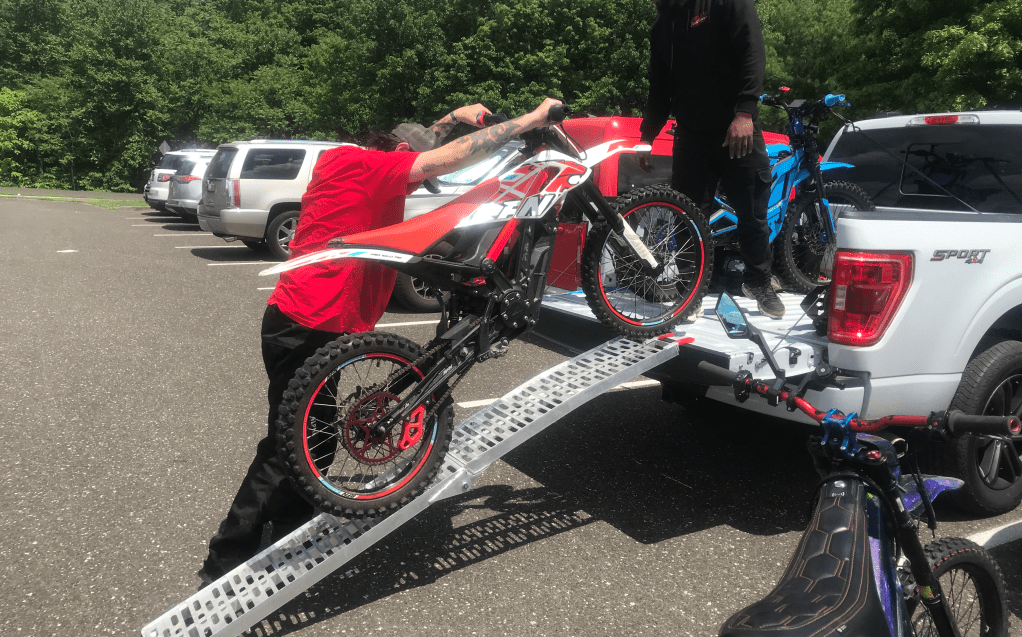

While unloading in a parking lot surrounded by a dozen ball fields, tennis courts and other mundane ways to spend a Sunday, the hypocrisy of sanctioned-versus-stigmatized hobbies hurts. This world-class park was once another sand pit and place to dirt ride, since snatched up by developers and put to a different sporting use. Tie-down straps stripped away and clanking aluminum ramps unfurled, the only thing missing were gas cans as the mid-range machinery that constitutes affordable electric dirt bike riding in 2024 rolled backwards down the bed of the Ford with its “Combat Veteran” license plate frame. At this stage of the game, I know enough not to ask. The marketing copy for this trio of electric test bikes is quite self-aware in its much-needed promises: “unlimited possibilities while reducing environmental impact.” How about: “establishing a new standard in this fiercely competitive arena.” Maybe you prefer: “effortless maneuverability, a fashionable appearance, and cheap cost.” E Ride Pro, Talaria, RFN. True, none have the household ring of brands that also build pianos, weed wackers and jet skis… not yet, at least.

So what’s beyond the Tron-like styling of these whiz-bangers? Which one is the best way to spend either side of $5,000? And, will future generations still be able to blow up berms without pissing off the neighbors? That is, if there’s a speck of land left to explore rather than exploit. As automotive power plants begin the great mandated migration (or at least diversification) away from internal combustion, motorcycles still lack the heir apparent: a mass-produced, effective, affordable and widely-recognized alternative to meet the broad needs of dirt riders at this critical junction while also appeasing Johnny Law and Jane Doe. So screw it. If you can’t beat ‘em, leave ‘em. Warm up the warp drive, boys, because we just passed the point of no return and these electric dirt bikes are headed back in time. I love the smell of lithium in the morning. It smells like… stealth.

The Sands of Time

A hole in the earth hidden in plain sight. A ghost town Garden of Eden, now an albatross around the zoning board’s neck. In the grand scheme of things, it’s utterly inconsequential yet it limps along to represent the current crucible of off-road riding. I’d previously hit on the history of this nondescript sand pit – a rapid-absorbing layer of Cohansey sand, some 100 to 250 feet thick made up of quartz, gravel and light-colored clay – when discussing the proactive preservation of dirt riding options. In short: contribute to the economy, don’t annoy the locals and present a positive public image. Moreover, a good portion of the comments on that story alluded to the opportunities electric dirt bikes might present so, like General MacArthur, we’ve returned. The final chapter of our test site, the former Blackwood Moto Enduro club, was written four decades ago. It has somehow sat barren all these years since, the sands of time just barely ticking by inside the hourglass. Millions of dollars have been exchanged, but the ground never broken – a rarity here when new construction is now closing in from all sides. A police firing range, public park annex, cemetery, in-patient drug rehab and now storage facility have all been floated, but this swath still sits. Even the “Superfund” landfill site next door, once one of the nation’s most notorious toxic sites, has been transformed into a solar energy park in the same timeframe.

So for the first half of 2024, beginning on New Year’s Day and clocking 160 miles all told of back-and-forth bicycles rides just to feel something like Thoreau at Walden Pond, I patiently waited. In turn, I met the people who’ve been squeezed out, pushed aside and passed over when opinions are weighed so decisions can be made. The teen from Camden who garaged his bike locally and just wanted to ride dirt – not do wheelies down the middle of Main Street and get his prized possession impounded. The tykes putting around on even smaller quads whose parents basically walked next to them. The trail riders with no feasible motorcycle transportation to the only off-road options 45 minutes away. Sitting at a town council meeting to practice journalism at 9 p.m. on a Tuesday as local residents tried to understand how another buck-forty of residential and commercial acreage in their back forty fit into the master plan’s land preservation goals, it was painfully obvious that dirt bikers aren’t the only ones with a list of grievances.

“Back then, we rode anywhere,” said Glenn Robbins, a former pro motocrosser who put on two riding clinics at the old track and donated every dollar and then some back to plowing and bulldozing the whooped-out circuit. After all, this was his riding spot, too. What was unique about this dime-a-dozen pit was that its late president and founder worked for the Catholic Church’s neighboring CYO youth program. After partnering with the club’s original pitch man and then convincing the Holy See to lease a portion of their land – with the non-profit organization officially hitting state books on Sept. 12, 1974 – an effort to formally organize the chaos of free riding began, Robbins said. This at least got everyone going in the same direction: “That was priceless to us.” Thus, the state’s first true off-road riding park with an annual membership-based system for a meager $5 per year was born. To hear his contemporaries say it, a Maico-mounted Robbins was a sight to behold and simply stupid fast in his day. “Go around the track and squeeze your grips as hard as you can,” he’d tell the students. “They’d come back and I’d ask ‘how do you feel?’ and they’d say ‘Terrible!’” He laughed heartily on our call. “Obviously! That was the idea,” he said of the 45-minute moto era.

‘It was the best place to practice in the state of New Jersey – an elite place to practice and train. It was well-organized, it was safe, and it was mobbed.’

If Robbins helped dial in the “moto” aspect, former Trail Rider Magazine publisher Paul Clipper’s allegiance eventually went to the “enduro” side of things. “Blackwood Moto Enduro was the place where I learned how to ride a dirt bike,” Clipper told me after I stumbled upon mention of a chilly New Year’s Day ride at “the pit” in his compilation book of “Last Over” columns. “The original track, which seemed to be all left-hand turns if you went the right way on the course, was improved over time and another group of guys arrowed out a set of tight ‘enduro’ trails that I thought was a lot more interesting than the MX course.” The whole thing “became a most comfortable place to hang out on the weekend” before broader horizons deep in the Jersey pines, and later California, appeared.

Clipper, barely a teenager around 1970 prior to the pit’s quasi-self-governing era, would beat up a stripped-down Suzuki TS250 Savage and Yamaha AT-1 with three older associates he’d met. The trio, with a hiking boots and blue jeans-clad Clipper in tow, took turns haplessly circulating the deep sand of the tire-lined track “falling down 12 times per lap, which of course means getting the bike back up, restarting it, and then railing off to the next corner. It didn’t take long to get tired at that rate,” he joked. They’d ride until exhaustion reigned and the poor primitive “all-purpose” bikes, sans lighting components, had been flogged within thousands-of-an-inch of usefulness. Blackwood introduced him to like-minded youth, old members taken too soon and woods riders who knew how to link trails together and cover as much diverse terrain as possible in a single ride. Ending 25 miles away at an old tavern didn’t hurt, the experience turning him into an “enduro rider for life.”

The club existed in its wide-open glory for a decade. There were motocross schools, field trips on chartered busses to professional races, poker runs, alley cat enduros making the most of neighboring woodlands and even the occasional trials competition complete with scoring. All this and more until, as the club’s original founder explained in 2025, insurance coverage continued to rise. Same as it ever was, personal injury lawyers got a whiff of blood in the water and a lawsuit over alleged injuries brought down the improbable agreement. The lease ceased, the club folded and the axe finally fell six months later when a priest complained to the local archdiocese that people were still parking and riding there. “It was the best place to practice in the state of New Jersey – an elite place to practice and train,” Robbins recollected of a spot where the likes of Tony DiStefano, Bob Hannah and even Bruce Jenner for a daytime talk show TV spot turned laps. Today, in an irony of all ironies, you can take a three-day motorcycle safety course in the county college parking lot across the street. What once existed on the other side of the road, now a lonely example of what could have been, is almost certainly unbeknownst to every participant. Robbins’ last pro race was in 1978 at the Montreal Olympic Stadium and his final twist of the wrist at Blackwood was the early 1980s. He’s never been back, not even to look at what little is left, but the legacy is not the least bit diminished in his view. “It was well-organized, it was safe, and it was mobbed.” Emphasis his. Envy mine.

Fifty years later, deep in the woods and down the hill from where the unlikely arrangement with the local diocese was first struck, this plot seemingly sits in purgatory in perpetuity. Are e-dirt bikes the salvation that could shepherd in a new era and deliver the sport from sin? Robbins couldn’t understand how electric bicycles would ever catch on. Now there’s one at home in the garage. “I think it’s going to be the wave of the future,” he said when asked about this little e-bike experiment out in his old stomping grounds. There’s an undeniable temptation of these whisper-quiet weapons of war weighed against the damnation of ditching your roots. Forgive us our sins, but this disobedience is exactly how Milton’s paradise was lost. All it took was a biblical battle on the sweeping plains of Heaven to reclaim it. Enough of the poetic waxing. Let’s get down to brass tacks.

Silent Weapons for Quiet Wars

It was an inauspicious start: the mountain bikers bound for single track did double-takes, the little kids sported a familiar form of envy and the rest of the chaperons with their prying eyes wanted to figure out why these supposed menace-to-society dirt bikes were so damn quiet. This is not a scientific Wired magazine piece with a dyno chart and dissected power bank. You can stop reading right now, go buy one on Marketplace and draw conclusions the same way I did. Furthermore, the difficulties of trying to tour on an electric street bike (read: rapid and readily-found charging stations) don’t apply here, either. What this piece provides, at an admitted minimum, are gut-reactions to the next big thing rammed right through the bore of a second-hand nostalgia pipe dream.

If two-strokes are chainsaws from Home Depot, these three e-dirt bikes were Harbor Freight power drills helping to get the job done. These aren’t plodding pedal-assist bikes, nor are they race-grade options coming to a stadium near you in the near future. This was more ripping a moped around town as if it were the Isle of Man and I was grinning like a fool by shootout’s end. Feel bad for your neighbors? A few grand burning a hole in your pocket? These “cheaper” options won’t change your life, but they’ll kill some time and keep you fit. In a world of power-regenerative braking, full charge from flat takes between two and three hours. Replenish the battery, saddle up on the electrified mercy seat, modulate the throttle to communicate with the controller, spin the brushless electric motor, rotate the rear wheel forward toward a maximum of 50 to 60mph and you’re off. Talaria and E Ride Pro claim a 50-mile range while RFN calculated closer to 100 miles if riding at 12.5mph on flat pavement; expect less than that from aggressive dirt riding. There was no Surron in this shootout but having logged a few laps on one elsewhere, we’ll say it felt closer ergonomically and performance-wise to the Talaria X3 than the E Ride Pro or Apollo Motor’s RFN… so we’ll start there.

This Talaria X3, developed by the 28-year-old China-based brand, was nimble enough to flick and sported basic knobbies on stock 17-inch rims that had carried it through state forest trail rides. It didn’t quite have the get-up-and-go of the others, as evidenced by the battery voltage, and a cramped cockpit did no favors.

- On the spec sheet:

- 60-volt, 40Ah battery

- 110 lbs

- seat height: 31.7 inches

- wheelbase: 49.4 inches

The Ares Rally Pro from the China-based RFN is the most traditional-looking of the bunch… until you actually eye it up in person. Throw a leg over and its stretched wheelbase and a low stock handlebar rise contributed toward the feel of an adult-sized pit bike at best.

- On the spec sheet:

- 74-volt, 35Ah battery

- 149 lbs

- seat height: 33.8 inches

- wheelbase: 52.36 inches

Finally, the top-dollar, largest-of-the-bunch E Ride Pro SS 2.0, which got the most seat time on test day. With a laden seat height of about 32 inches, handlebar risers and sporting an aftermarket 21/18-inch Luna Cycle wheelset with Dunlop knobbies wrapped around the rims, this additional $450 investment on top of the $5,000 base price made a major difference.

- On the spec sheet:

- 72-volt, 40Ah battery

- 139 lbs

- seat height: 32 inches

- wheelbase: 50 inches

If you’re capable of being convinced and still on the fence, hop off. While trying to line up one turn’s exit with the next rutted berm, foot out and jamming the left-hand rear brake lever like a clutch to get through the downhill slalom, the absolute last thing on my mind was gauging speed by the sound and feel of RPMs. I stomped for a brake pedal that wasn’t there exactly one time, and accepted these bikes for what they are: slightly different where suspension movement, chain slap and motor whine provide all the feedback. By the end of the test, the forks on the E-Ride were wonked-out in a fall, the handlebars on the RFN were bent in a jump attempt that came up short and something loose on the Talaria was jumping teeth under power. No shortage of tinkering to be done back at the garage – and that’s an important distinction for those who dismiss battery power as the equivalent of idiot lights on the car dash.

This wasn’t the fairest of fights, but it was in the ballpark price and purpose-wise. The E Ride Pro SS 2.0, box stock in the power hop-up department, was the most motorcycle-like when ridden in anger. It had light switch-like power qualities, could cover straight-line distances at a good clip, explode out of turns as hard as you could whiskey throttle it and generally instill a modicum of confidence due to its stature. It’s no 80-horse Stark Varg, but it doesn’t have a $13,000 suggested retail price, either. Then there’s Yamaha’s still-in-development EMX’er, just one example of what’s inbound from overseas, where recently-published patents suggest “it’s getting close to completion.” To commit to buying here and now – with third-party online storefronts loaded with promises about plentiful stock and fast shipping – is more of a battle of keeping computer hardware current than investing in a motorcycle you may own for a decade. You could wait for the next big thing but by then, there will already be another new graphics card… er… high-voltage battery about to be released. As for our E Ride here, I got a text message two months after the test telling me it was for sale… and the $5,000 Marketplace listing didn’t last very long.

No Sympathy for the Devil

Now let’s trade that silent and serene hallowed ground for pretty much pure hell. It’s 100 degrees and hasn’t rained in weeks. We’re in another de-forested shade-free site in some other forgotten corner of New Jersey and the motocross riders in full-length riding kits are whipping up cyclones of sand that never land. There’s no need for hyperbole at this point, but one fire-red Jersey Devil is commanding my attention inside Dante’s eight circle of the inferno. It’s a Stark Varg owned by Erm Centofanti, a Monmouth County, New Jersey resident who has come down to the Field of Dreams MX park for a race weekend. “This is the best motorcycle I’ve ever owned,” the lifelong rider and 50-plus racer said between sessions in a highly-desirable shaded corner. “It can be a 125, a 250, a 450 or a 500,” he added of the Varg’s on-the-fly mode adjustments.

Field of Dreams clearly states on its website that it’ll only allow electric dirt bikes manufactured by “major” companies and that they “must have proper tires and adjustable suspension.” You aren’t getting on their track or trails with anything less than Surron’s Storm Bee or Light Bee X, both of which were a few spec sheet notches and few thousand dollars up from our three earlier test rigs. The problem, facility owners Chris and Lexi Andersen explained to me, is actually multi-faceted. “People think of it as a bicycle,” Chris said of those pushing 60mph without a helmet or any sort of licensing. Lexi adds that that they tried to do an electric bike fun run on the site’s smallest course. The Surrons and their ilk almost immediately bent vital components that would keep them tracking true. Having seen the same exact scenario unfold when our test RFN flubbed a jump, I believe it.

The final issue, “believe it or not,” Chris pauses to preface, is that “you can’t hear a rider coming up on you.” This is the biggie that keeps the Vargs out of homologated race registration both here and at Raceway Park, also an AMA District 2 track. Lexi echoes that a flagger who may be attending to another rider’s problem wouldn’t hear an approaching electric machine, which endangers everyone in the hypothetical scenario. Watching intently as the Varg dug in and spit out during its Saturday sessions, it did so in mesmerizing (and oddly satisfying) silence. Hate to say it, but the mid-2000s blue smoke-belching Suzuki RM looked absolutely antiquated next to it.

“I don’t buy it,” Centofanti said of the silent treatment, adding that he’s sold the rest of his fleet and has fully committed himself to this beast. A stroke of good luck (pun intended) and a few loops around the parking lot later and the difference between even the $5,000 E Ride Pro – of which there was one in the FOD pits that received high praise from its B-class rider as a side hack – is just painfully obvious. This is a full-size and full-power motocross machine that feels like a dirt bike, rear brake foot lever on the right and all. What lifelong rider and racer Centofanti has tried to convince local track owners and the regional AMA racing district is that there needs to be an electric class and soon; the major players at the big four overseas brands are going to see to it anyway. Setting any personal preferences aside, it’s hard to dismiss these game-changing electric bikes as a flash-in-the-pan fad. “No sympathy for the devil, keep that in mind,” the author of Hell’s Angels, Hunter S. Thompson, once said. It’s just that what he uttered in the next breath isn’t quite adding up.

Buy the Ticket, Take The Ride

Yeah, ol’ HST was talking about hard drugs (what else?) when he cautioned those who’d shell out the cash, but were unprepared to deal with the fallout of their own free will. That the best interests of these silent machines are falling on deaf ears is beyond ironic. “We need an alternative. We need the AM-B,” Centofanti said on that blazing hot Saturday, adding that promoters could theoretically run an AMA-OK’d electric-only class at 9 a.m., not violate any sound ordinances then get on with the full dawn-to-dusk 22-race day that FOD had lined up for Sunday. While he won’t be rolling the Varg to the gate on race day, he’ll still be here all weekend, getting as much seat time as possible on practice day. So why not just go home and save some camping fees? “I love it. I can’t let it go. It’s part of who I am.”

Pandora’s box is open. The genie is out of the bottle. Whatever you want to call it, there’s the eMoto class of the Red Bull Tennessee Knockout, with Surron as a presenting sponsor; E Ride Pro backing electric-only races at Glen Helen (the same track that hosts the Two Stroke World Championships – go figure); MXGP’s support class in 2026; and the FIM’s MotoE road racing as just a few examples of the diversity yet to come. But competition costs, and spectating one of these events can be about as frustratingly quiet as a bicycle race. What’s needed is a cheap local sand box to play in, a place to pit ride and have fun – which only reinforces the concept of our earlier shootout: a test of verboten setting versus battery life under load.

We also knocked a third bird out of the sky in the process: the long-festering problem of access to cheap, local and legal off-road riding areas continuing to trend in a negative direction. The owners of the three test bikes said they’d respectfully ridden pretty much anywhere and on the off chance they were stopped by cops, all they got was a rather friendly warning to not play in traffic on an e-bike. It’s no wonder that so many I met through this experiment, already entrenched as outcasts, attested to going cloak-and-dagger when they can and where they can while they still can. I spent my formative years on four wheels, not two. Skateboarding’s long road from last bastion of misfits to bona fide Olympic sport – where we finally figured out the balance between bland man-made parks and destroying public property downtown – is a book chapter for another day. You can’t fight City Hall but maybe these new electric bikes, with their re-chargeable batteries and out-of-sight, out-of-mind, emissions-friendly possibilities, will partially appeal to politically-correct sensibilities and rekindle the days when any old unimproved lot of land was fair game.

‘Look at how many golf courses there are in New Jersey. We could ride on any one of them.’

Is this a coastal-only problem in the US, or are the over-developed and over-populated regions to the extreme east and west just canaries in a coal mine? We can’t all live free or die. Here in the “garden state,” a moniker that becomes progressively less true by the year, the noose is being fashioned as lawmakers mull registration and insurance for e-bikes while off-road access within Wharton State Forest continues to be curtailed. “Look at how many golf courses there are in New Jersey,” Centofanti said. “We could ride on any one of them.” That I’ve raced off-road bicycles on a very recently defunct, but still clearly identifiable, golf course gives his claim a lot of credit. As the old political slogan went: a chicken in every pot, a car in every driveway an electric dirt bike park in every community – and why not? Remove the need for massive noise buffers and you’ve got an entire generation of bottom line-boosting future customers feeding projected profit margins. It’s the American way.

The Wasteland

The dead land. The cactus land. Across T.S. Eliot’s hollowed-out post-war wastelands, there’s sprawl between the act of actually doing something and the motions to make it happen. We put three affordable e-dirt bikes inside a sandstorm where the rain of red grains obscured past, present and future. We were out of earshot before even being out of sight, immediately immersed in such an odd juxtaposition of time and place that it shouldn’t still exist… and yet. You devote so much effort into understanding jetting, timing and feeler gauge play for a bike to come along that can plug into a wall outlet overnight and be ready to rip in the morning. It sounds too good to be true because it is, and we’re still not out of the proverbial woods.

The late Rick “Super Hunky” Sieman, Dirt Bike magazine founder and life-long advocate of equitable access for off-road riding on under-utilized land, said it best. In a departure from his gonzo-like approach to motorcycles and the editorial magazine world, “No Trespassing!” is a solemn column where you could tell it still stung. “It made me think back to the days of when I was learning to ride a dirt bike,” he wrote after passing a cacophony of kids on clapped-out dirt bikes tearing up some unused patch of land. “And it made me appreciate that vacant dirt lot a great deal.” Here in this “crummy looking area” that eventually “grew on you,” with its trash dump neighbor upwind, industrial refuse all around and S-curves through the deep sand, was paradise tucked away in a secluded setting. Sieman said everyone has got to start somewhere and they invariably “learned the basics on a ratty machine on a piece of desolate ground that nobody was using at the moment.”

‘It made me think back to the days of when I was learning to ride a dirt bike. And it made me appreciate that vacant dirt lot a great deal.’

“And, like all of us at one time or another, they were threatened or thrown off that unused piece of land, for one reason or another.” All the good years that flew by culminated with one very bad day. The foreboding signs, threats of fines and barbed wire go up, and the morale goes down as an unused patch of dirt suddenly sits silent. “That night, and for a long time after,” Sieman wrote to close his column, “I felt very small and helpless.”

Somewhere in the fear and dark of Eliot’s lost kingdom, this twilight of the gods where electric evolution holds a lethal Taser to the temple of top dead center tradition, is an overgrown path to push things forward. There are even old enduro arrows nailed to the trees showing you the way out if you know where to look. With patience and persistence, paradise lost can be found – but only for a few hours. Here’s the thing. If a bunch of electric dirt bikes churn up the sands of time inside this dead valley but there’s no one around to hear them, do they even make a sound? Eliot didn’t think so. This must be the way the world ends then… not with a bang, but a whisper.