When all the branded road signs negate the need for GPS, when a stack of calendars count your years in operation and when the track-side luxury condo-garages keep filling up, that shining business on a hill has hit its north star.

New Jersey Motorsports Park (NJMP), arguably the city of Millville’s highest-profile podium-topper in terms of tourism, was the site of the sixth round of the 2024 Bridgestone Tires AHRMA Roadracing Series. This makes it another name on the map no different than Bloomingdale or Birmingham at either end of this year’s schedule. Millville: It’s about an hour south of Philadelphia, the home plate of Major League Baseball’s favorite son, Mike Trout, and home base of the P-47 Thunderbolt. It’s the kind of home-away-from-home readers of this magazine root for outside of their annual visit and “Holly City” locals know deep down is always just about to turn that corner toward prosperity. Thing is, “crown jewel,” “hidden gem” or “diamond in the rough” boils right down to who you ask and we picked a real pressure cooker, a trio of triple-digit days during the first weekend of summer, to find out.

“It’s the anchor,” Daniel May, AHRMA’s black leather-clad executive director, said of NJMP’s undisputed significance and why in god’s name we were smack dab in hell. His BMW boxer clinked as it cooled post-practice while racers draped themselves over box fans on blast like it was some sort of bivouac. Perish the thought, but in an economically battered city like Millville – where financial assistance from “Empowerment Zone” corporations and payments in lieu of taxes are designed to level the playing field – few things come easy. So, for the remainder of this piece, consider that similar hard-luck town near you and where else your getaway dollars go besides $3.29 a gallon, Gatorade and the gold medal.

Dateline

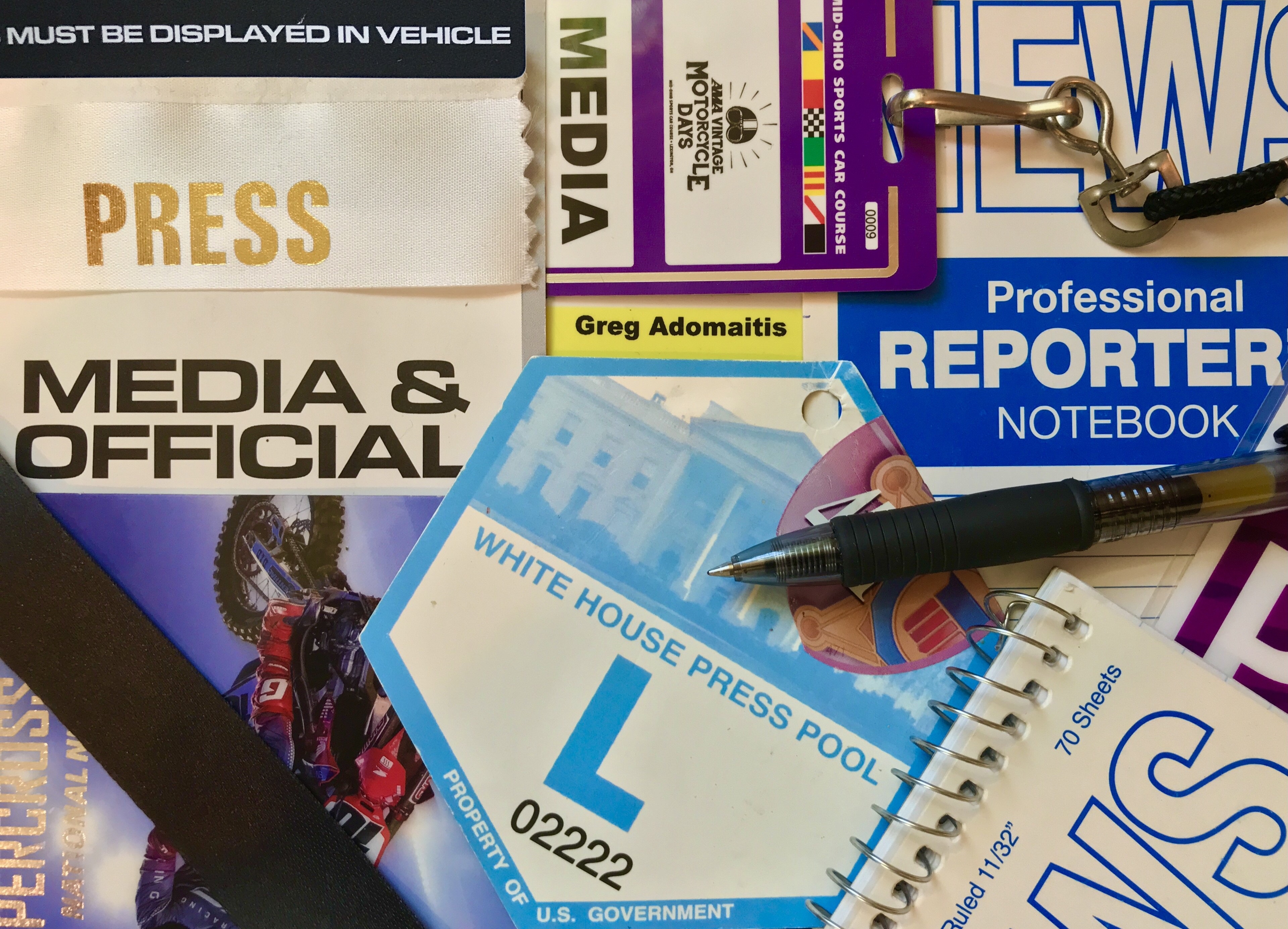

Millville and its 28,000 residents loom large in Cumberland County, always maligned as the poorest part of tax-happy New Jersey. The region – a blend of bayshore fishing, migrant-fueled farming and three urban centers – was always floundering in bad news. The aftershocks of a once-in-a-lifetime global economic disaster (no, not this one, the other one) were not an ideal time to enter the full-time job market but, for $425 a week, there it stood: a May 27, 2010 voicemail and an offer to be a local newspaper reporter. I’ve been out of the game for as long as I was in, but seven years is 2,500 days of morning, night, weekend and holiday coverage of Millville’s topical to tragic: gangland gunplay, contentious council meetings, a local radio host’s triumphant return and a bucket list flight aboard a Boeing B-17 Flying Fortress out of the airstrip next to NJMP.

My former paper put out an in-depth read last summer chronicling the crisis: “This forgotten N.J. county is worse off than parts of Appalachia. How can that be?” We’ll get to that in a moment. Presumably reading the writing on the pit board, Millville leaders have put many of their eggs into the gear head’s clutch basket and you know what… it’s working. The modern motocross facility just across the street from NJMP was buzzing with activity while AHRMA’s event unfolded in perfect earshot across the tree line. Want to race go-karts for bachelor weekend, hit bike night and live music at the on-site pub or watch the Blue Angels do their thing? Like the sign said on the weaving way out, “life is better at the track” and we don’t disagree. For those who crave the cacophony of fire and steel, it’s Millville or bust.

Life is Better at the Track

The sincerity of Omarey Williams, the county’s shared services coordinator, shone through in just about everything he said. “The race track is supremely important and it has brought in a lot of tourism and business. I would say it’s one of the jewels.” Millville’s historic stage theater, quaint cottage shopping village and longstanding arts center offer up a few more veins to tap in this tangled thing called tourism. “Everything is within arm’s reach if they want to branch out,” he said of getting visitors and locals alike to explore options beyond their primary destination.

Enough with the Econ 101. This is, after all, a magazine about motorcycle racing. The weekend of June 21 through 23 was, in a word, (really) hot and as a fair-weather road rider these days, I don’t know how the full-body racing suit gang gets down. The heat radiates in waves, a blurred mirage off the recently repaved 2.25-mile, 12-turn Thunderbolt course. A high-strung engine begins to breathe in a decrescendo that bangs down the ‘box. Teenage flaggers on summer job duty ask how old my trusty twin, the wristwatch-reliable ‘74 GT185, is. There’s the futile whine of roll-start machines and the shoulder-to-shoulder shade in rented paddocks where tire warmers finish the job that 100 degrees could not. There are copious notes, Sharpie scribbles and slivers of tape all over these machines: carburetor jet sizes scrawled on the float bowl, race numbers, grid position, the classic “fuel on/off?” and some mathematical equation I couldn’t quite make out on a gas cap.

Up close, nudging the red-white-red-white apex for position, roadracing is as subtle as buckshot. Exposed crank-ends on some of the many RDs and TZs whirling away as operators kept the fires lit under adverse carburation conditions, the GSXRs, FZRs and CBRs of the “Next Gen” late-1980s/early ‘90s power in plastic era, and the modern-leaning, neck-twisting Sound of Singles, Battle of Twins and Sound of Thunder races. In fact, the entry list for that latter trio of Millennium-era and up bikes takes up a mighty large chunk of the results and arguably assists with keeping this race on the… uh… road.

‘The race track is supremely important and it has brought in a lot of tourism and business. I would say it’s one of the jewels.’

Mom and Pop Stops

Exit the main highway headed south toward the track and the “Welcome, Race Fans” billboard atmosphere comes on the pipe real quick: fuel, food, lodging and all those last bits of local flavor in exchange for a few hundred dollars before the gate fees hit your bank account. If one is going to drive 900 miles from West Bend, Wisconsin to Millville and take three days to do so, Pat and Kat Hanson of Grid Iron Racing have the logistics nailed down. “We supplied up in Millville. We purchased all our food for the weekend. We had lunch in town,” Pat said. “You don’t want to have to pull the extra weight if you don’t have to. Every time you bring in a race, you have people buying supplies.” The story at Blackhawk Farms Raceway in Illinois “is about the same type of economic situation,” he added. “The race track is a big draw, especially for amateur cars and bikes.”

Charity Giovanelli, who has worked for NJMP since its 2008 inception, is director of the Rider’s Club and track operations manger for two-wheeled events. More importantly, at least in the perspective of this piece, she lives in nearby Lawrence Township and understands the region. “[Racers] stay at hotels, they eat at restaurants. There’s always people coming through the paddock asking, ‘Hey, where’s a good place to eat? A mom-and-pop place?’” She estimated about 300 attendees would come through the gates for this weekend; that headcount swells to 2,000 for MotoAmerica, which returns in September. With that big-ticket event, superbike fans from around the tri-state region of Delaware and Pennsylvania once again pay to play in – where else? – Millville.

“NJMP is proud to make racing and the world of motorsports accessible for the community,” said Brad Scott, the track’s president and chief operating officer. “Ever since we opened in 2008, NJMP has worked to create epic events, like AHRMA, that appeal to those local to Cumberland County and to those traveling from out-of-state. And with each year we are thrilled to see new and returning guests to our park and the county.” Thread the compression tester into the beating heart of America’s economic engine and this is what keeps it out of the red. For perspective, statistics published by the track show NJMP in 2016 paid $2.1 million in salaries and wages, paid $275,000 in property taxes and spent $1.2 million with vendors in Cumberland County. That splash of liquid cash is the trickle-down fuel this economic engine needs to keep firing because in Millville and the surrounding communities, there weren’t enough bootstraps in the world to stop the “giant sucking sound,” as Ross Perot said in 1992, from taking good-paying, easily-attainable and long-lasting generational factory jobs down the drain.

‘There’s always people coming through the paddock asking, ‘Hey, where’s a good place to eat? A mom-and-pop place?’

You Can’t Go Home Again

You could write this same story about Gettysburg. Virginia International Raceway’s 270,000 annual visitors, the $403 million Road America generates for Wisconsin annually and Heartland Motorsports Park having some 230 “event days” each year in Kansas would also work. Williams, the county tourism coordinator, said high-profile events help regional businesses to improve services, hire more staff and boost foot traffic while encouraging other entrepreneurs to give it a go as a marketing opportunity begins to twist together like so much safety wire. The host town needs that parasitic draw of racing; some might not like the noise, but you’ll like the revalued tax bill even less. The names Owens-Illinois, Ferracute Machine Company and Ardagh Glass don’t mean nothin’ to folks outside the area but here, one reveres the mere mention in one breath and curses their closures in the next.

“Every place, no matter where you go, will have its drawbacks,” Williams countered when we hit on this region’s hard knocks reputation and the planning/zoning pains of motorsport. “There is so much here that people don’t know about.” To wit, the bartender inside a very nearby brewery offering the first escape from five hours in the furnace shared his consensus on race fan overflow: “It depends on the event.” There were occasional visits from the track with trailers in tow, but nothing too profound. So we kept exploring.

It had been a long time since I walked the airstrip’s barbed wire fence neighboring the road race circuit. The humble military museum inside America’s first defense airport, where so many World War II bomber crews sat down 70 years later to share their stories, piped Big Band music over tinny speakers to an audience of one one. Standing next to a static display of a Vietnam-era battle tank, AHRMA’s symphony of speed played out downwind in the distance. Millville: it’s the place I bent Dave Mirra’s ear for a quote as he went RallyCross car racing for the sport’s first US foray, the place I bent a celeste blue Bianchi around the red-white-red-white apex and the place I bent the rules more than a decade ago to score a Flying Fortress flight “for a story.” They say you can’t go home again, but you can pay it forward. To the place that helped kick start a career and, in turn and in time, grew to feel something like a second home, it’s Millville or bust.